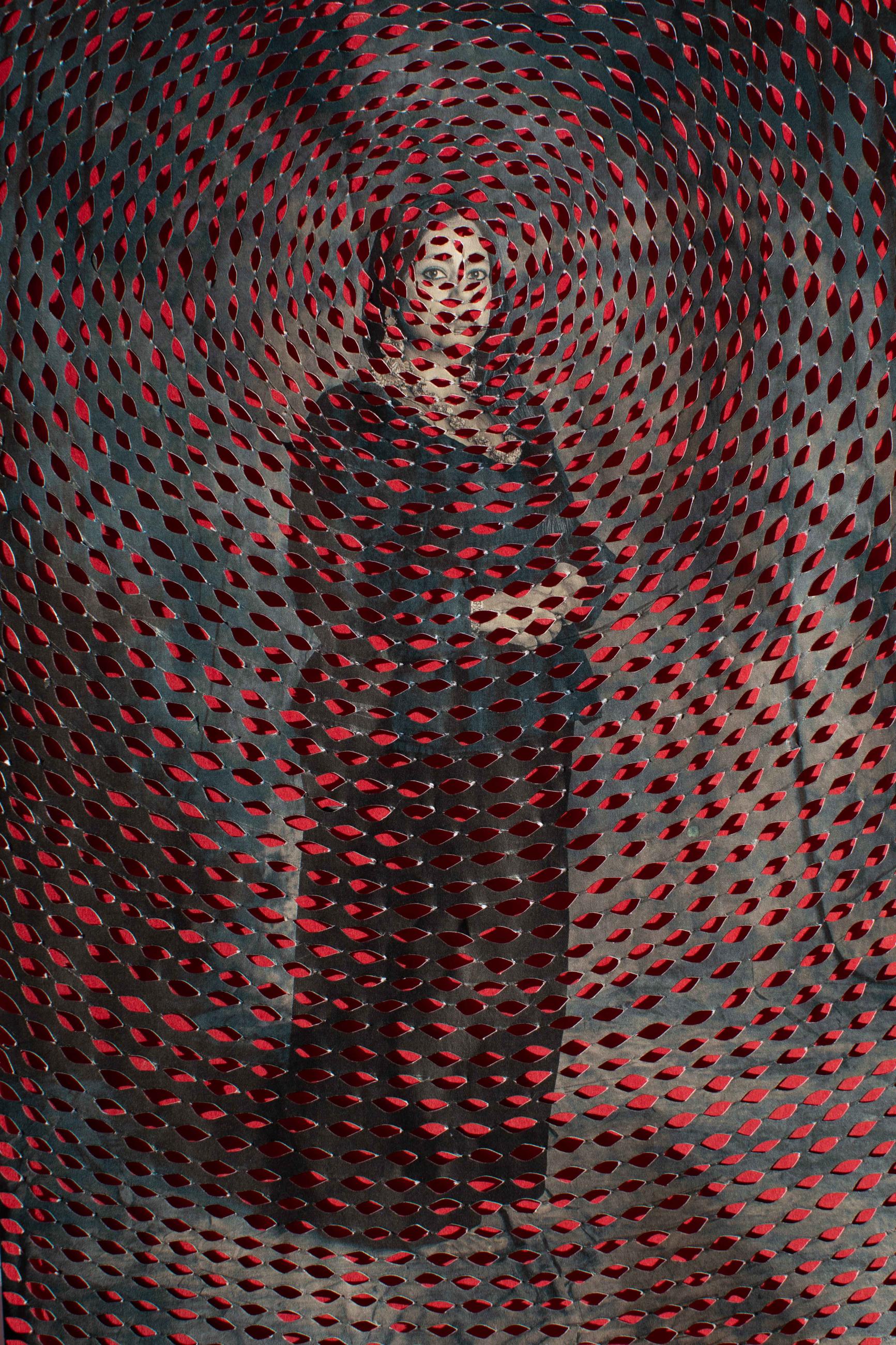

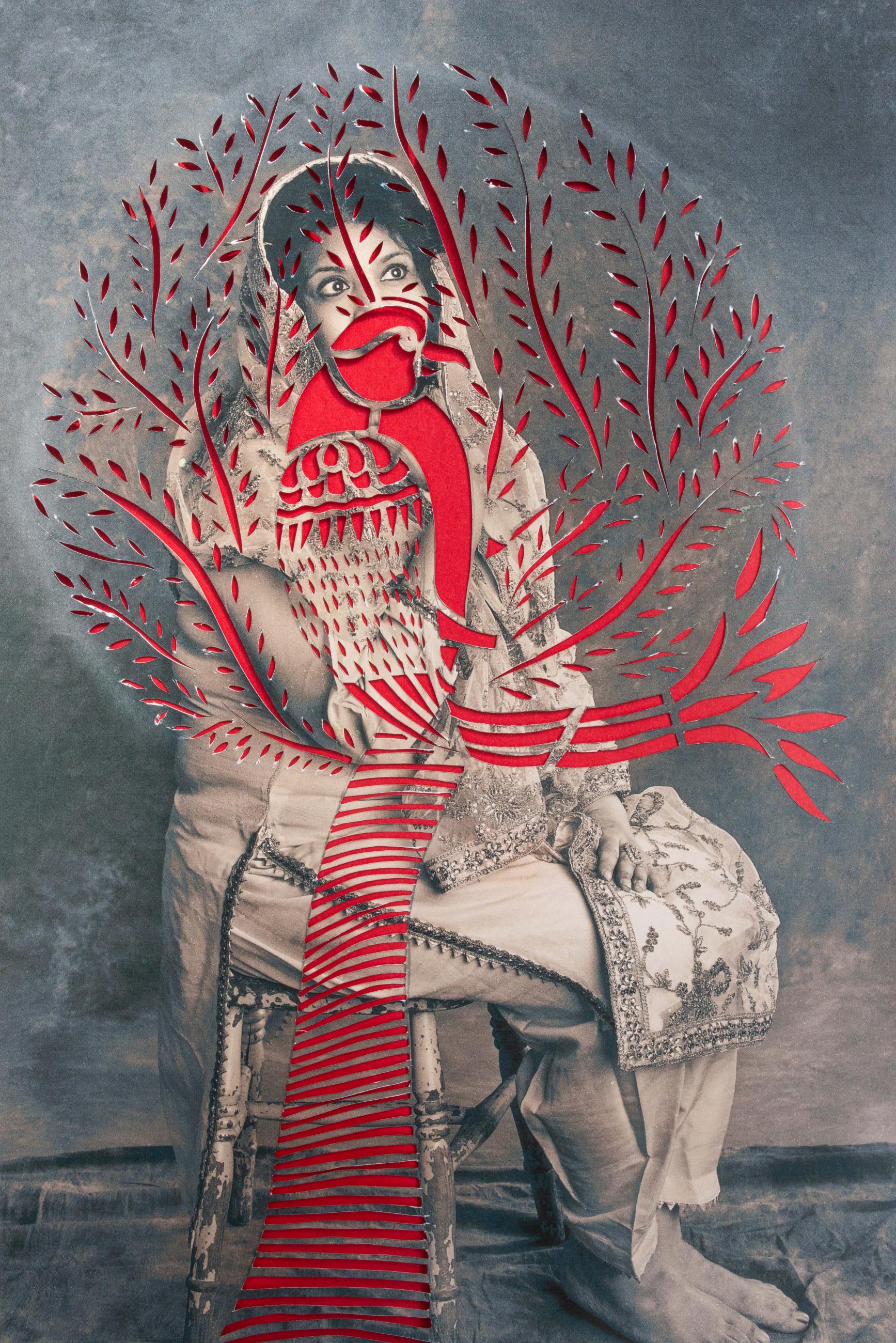

Derived from the ancient Asian form of torture of lingchi (known death by a thousand ), A Thousand Cuts is an ongoing series of portraits and stories that present a photographic study of patterns of domestic abuse in the South Asian community. I have borrowed the metaphorical meaning of lingchi to showcase the cyclical nature of domestic abuse. The continuous act of chipping at the soul of the abused is expressed by making cuts on the portrait of the participant, while the prints are made on thin paper to depict the fragility of the existence. The final artwork is photographed in a tight crop to create a sense of suffocation and absence of room for movement.

I am an Indian born – British photographer. In 2009 I completed masters in International Relations from King’s College London. I have a background in journalism that informs my research based practice. I combine traditional artistic interventions and photography to call attention to the boundary of cultural imperialism, a boundary marked not by the social exile of the “other,” but by the ordinary, the ever-present yet trivialised exile formed by prejudices so fundamental as to not even be noticed.

It was a happy childhood. My father protected us. We did everything he said. He said: ‘I dream of you growing up to be happily married.’ I had that dream too. He said to me: ‘Marry.’ I married. My partner abused me and asked me to leave. He won’t take me back now. I have no dream left.