Breaking Boundaries - Daniella Zalcman, Blink

Blink is a platform connecting thousands of media freelancers with publishers, brands and agencies who need high quality content produced on location anywhere in the world.

---

Daniella Zalcman is a documentary photographer focusing on the legacy of Western colonization. Along with being recently awarded 2016 Inge Morath Award, she also won 2016 FotoEvidence Book Award for her project, 'Signs of Your Identity', exploring the legacy of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools, which began operation in the late 1800s. She has worked as a traditional visual reporter before finding her own voice by embracing double exposure and adding a layer of narrative to her stories.

The Boreal Collective photographer talked to Blink’s Laurence Cornet about her projects and about breaking the formal boundaries of documentary.

Laurence: How did Echosight come about?

Daniella: I moved to London in 2012 and started a personal project, New York + London, which explored my nostalgia around leaving New York, and how familiarity dictates the way we photograph. The result was a series of double exposures; one image of New York and one of London melted together. Echosight was more or less the same concept, with a collaborative component. I was shooting in London while a partner, Danny Ghitis, was shooting in New York, and we would combine our photos. We did that every single day for about a year and it became a little overwhelming so, we started to have guest photographers take over the Instagram account for a week; we have had incredible people come in and play around -- Ed Kashi, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Barbara Davidson, David Guttenfelder, and Ruddy Roye to name a few.

Documentary photographers work with so many constraints; we are all constantly terrified of crossing the line of what’s considered ethical and appropriate. Echosight was a chance to completely drop all of that.

Laurence: In this specific context of two works totally dependent on each other, what are the merits and challenges of collaboration?

Daniella: It’s incredible how much each contributor brings to a project. When two separate visual thinkers communicate well, they produce incredible work. The photography community is a family. The more opportunities we have to work together and give each other feedback, the better our work can be.

At the same time, photography is everywhere. You have to do something extraordinarily different to get someone to stop and think about a story. I think that this is the reason why media outlets are now really receptive to alternative kinds of photography.

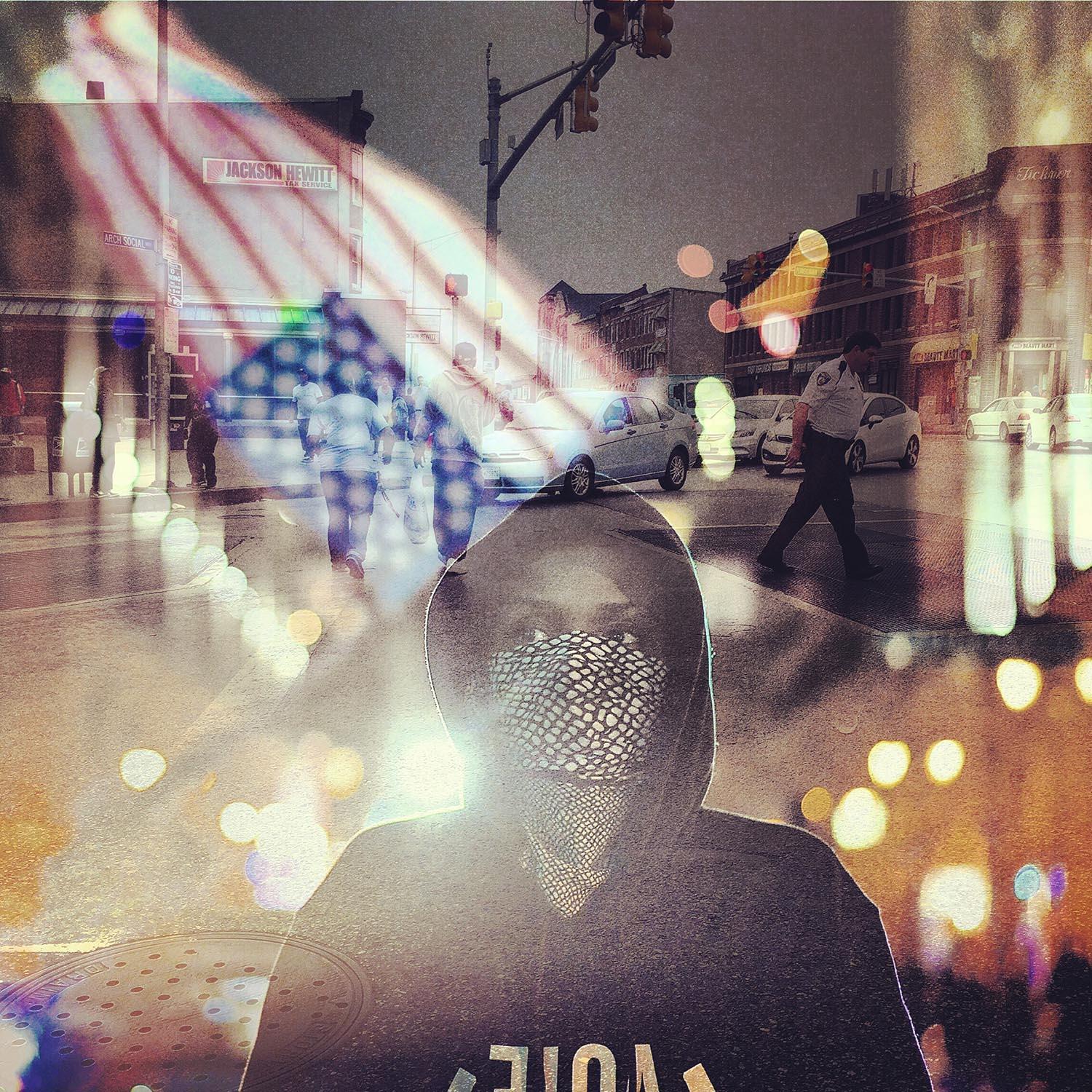

Two great editors from Al Jazeera America and I came up with this idea to document the first anniversary of the Ferguson shooting by having a young black photographer from Ferguson and a young black photographer from Baltimore take photos, and I blended their images into echosights. This was a great counterpoint to the work that came out of those two cities. Many of the journalists who went to cover those stories weren't familiar with the communities and didn’t necessarily understand the tensions that existed there — so we wanted the project to come from a place of more nuance.

Laurence: There is definitely an opportunity with double-exposure on the individual level as well. Can you talk about the narrative possibilities of double-exposure and why you started to include it in your documentary work?

Daniella: Double exposures add an extra layer of storytelling. For example, take my project on the residential school system in Canada, a series of boarding schools for indigenous children founded in the early 19th century. In brief, these schools intended to whitewash and forcefully assimilate indigenous kids who were kidnapped from their reservations. They would be forced to wear Western clothing and were not allowed to speak their own language, to practice their own religion or their own culture in any way. On top of that, there was rampant physical and sexual abuse. This story deals with the past and with memory and to me, a straight series of portraits wasn’t going to be enough to tell that story. So, I created multiple exposures with portraits and sites relevant to former students’ experiences.

Laurence: Can you talk about this issue of the First Nation in Canada, maybe in relation to contemporary migrations?

Daniella: Canada’s First Nations were the original residents and the Western Colonizers were the immigrants. Yet, these colonizers certainly never had any of the problems that modern immigrants face today. In the meantime, I live in the UK, which at one point was part of the biggest empire in human history, and I am ethnically Vietnamese and of Eastern European-Jewish heritage - so, as you can imagine there is a lot of imperialism involved in those two histories as well. I’ve always been fascinated by the ways in which either post-colonial or neo-colonial communities interact with that history.

In Canada, the thing that struck me the most is that the HIV rates among indigenous population is one of the highest in the world, and the infection rate continues to grow at a high speed. Reading through medical journals and articles before I got there I really couldn’t find any explanation. Then, I realized that every single HIV positive indigenous Canadian I spoke to had gone to residential school, and almost nothing was written on it. This school system existed in the U.S. as well. This seemed to me like a huge failure of the North American governments, educational systems and media that we had not managed to tell this terrible story.

Laurence: Talking about sensitive and under-reported issues, you also worked on the evolution of homophobia and anti-homosexuality laws in Uganda. Can you talk about the challenges you faced and the way you approached this subject?

Daniella: I’ve always been drawn to stories about sexual and gender identity because I think that is one of the defining human rights movements of my generation. I was on my way to South Sudan to cover the independence in 2011 and I happened to get to Kampala shortly after Uganda’s first and most prominent LGBT rights activists had been murdered.

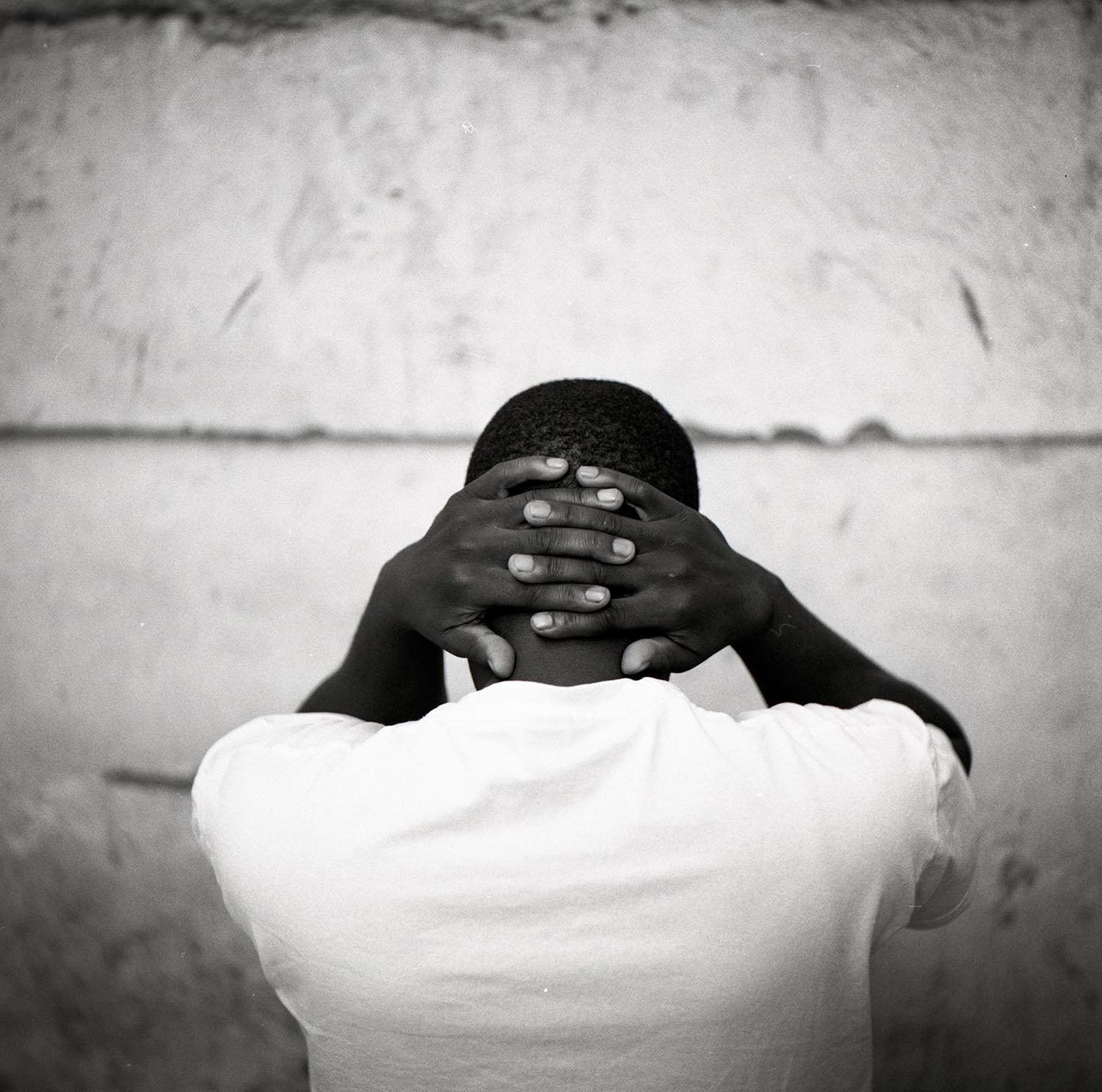

So I shot a series of portraits of LGBT rights activists in double exposure. All of them were out in Uganda and happy to have their faces visible, but Ugandan media often appropriates imagery from Western journalists and runs theses images under headlines like “kill the gays”. Double exposure was a way to avoid this.

Laurence: Before doing double exposure, you did a few series that blur the line between reportage and fiction, such as the re-enactors of World War II or even the eco-villagers. Can you talk about the relationship of fiction to your work?

Daniella: In the case of the World War II re-enactors project, there was obviously a huge fictional element. I drew that element out by shooting with a medium format camera that I love and is almost from the same period. In a sense, I was reenacting along with them.

The eco-village series is less about fiction and more about escape. While in New York during the Occupy Movement, I met people my age who were dissatisfied with their government and the status quo but I couldn’t get a coherent sense of what they wanted to change. When I met this group of thirty people living in the forest just outside of London, I could understand. On a very small scale, they created a solution. They were redefining how they wanted to live their lives. It so dramatically disagrees with what we all consider normal that it’s a fiction to some extent.

Laurence: You just became a member of Boreal Collective. How does it feel to be a part of a photo collective who has a non-formal approach to reportage as well?

Daniella: I’m so honored to be a part of Boreal and I think that my work fits in very well with the spirit of what members focus and work on. They all work on these slow, thoughtful explorations of identity and environment. I have a lot of respect for that because it’s increasingly difficult to do. We all have editors who want us to work quickly.

What photographers mostly need is a good collective conscience. Usually, we are very secretive about our work as we never want people to know what we are working on before it gets published because we are paranoid about someone stealing our ideas. So, it’s nice to have this trusted little family where I can send out a bunch of images and ask, “Does this make sense? Am I on the right track?”

Laurence: Is there anything you are looking forward to at the moment?

Daniella: The Canadian government created a Truth and Reconciliation Commission earlier this year, and one of the first recommendations was to educate children about what happened in residential schools.

So, I’m trying to create a photo book that can also function as a textbook. It would contain all these first person interviews along with First Nations scholars’ texts. A lot of kids are visual learners and relate much better to individual stories than they do to desiccated, generalized history. If I can get a book in front of a kid that has the photo of someone who went through this, I think there is a much greater chance for that child to empathize and remember. It could potentially be an incredibly important teaching tool.

Laurence: Be it with double exposure, fiction, or pedagogical tools, you break the constraints of reportage. Can you comment on the innovation and experimentation in photography for better storytelling?

Daniella: Right now, we are redefining the meaning of photojournalism and reportage. It’s funny how the World Press comes out with new stringent guidelines every year while I see more innovation and experimentation in photography.

Is my double exposure work reportage? Maybe not. Is it journalism? I think so. I’m not going to argue my case for whether or not I should be able to submit to photojournalism awards. More and more people are agreeing with me and are expanding the definition of reportage. Anastasia Taylor-Lind is currently working on a project where she sends a postcard from Donetsk, with the names of the people who fought and died in the war there. That’s not photojournalism at all, but its storytelling, and it’s incredibly powerful. Our vision is getting much broader and more exciting. I’m happy to be working on the end of the spectrum.

Interview by Laurence Cornet / [email protected]

Edited by Sahiba Chawdhary / [email protected]